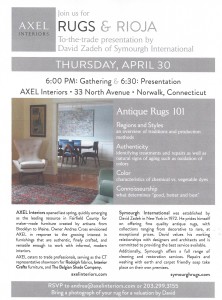

Please come and join us for an overview of traditions and production of antique rugs. Enjoy a glass of wine, while listening to what makes a rug good, better, or best.

Historic Night for Art

A Historic Night at Christie’s

I am thrilled to share that last night’s Evening Sale of Post-War and Contemporary Art achieved an unprecedented $691,583,000, the highest total for any auction in art market history. Bidders from 42 countries competed for iconic examples from all the major movements of the last six decades, underscoring the strong international demand for masterpieces of the highest levels. Ten new world auction record prices were achieved for Francis Bacon, Jeff Koons, Christopher Wool, Lucio Fontana, Donald Judd, Wade Guyton, Vija Celmins, Ad Reinhardt, Willem de Kooning and Wayne Thiebaud. Three works sold above $50 million, 16 above $10 million, and 56 above $1 million.

The top lot of the sale was Francis Bacon’s triptych, Three Studies of Lucian Freud, which inspired a 10-minute bidding war and saw multiple bidders bring it up to and over the $100 million mark. The crowd burst into applause when the hammer came down at $142,405,000, a world auction record for any work of art ever sold at auction. The work is one of the most important paintings by Bacon, uniting two of the 20th century’s greatest figurative painters at the apex of their relationship.

Spectacular results were also achieved for two masters of Pop. Jeff Koons’s Balloon Dog (Orange) achieved $58,405,000 (estimate: $35,000,000-55,000,000), a new world auction record for a living artist, and the most expensive contemporary sculpture ever sold. Andy Warhol shone throughout the sale with seven works produced at key moments in his career. One of the highlights was his hand-painted Coca-Cola bottle, one of his earliest works which went on to inspire the beginnings of Pop Art in America. The work realized $57,285,000 (estimate: $40,000,000-60,000,000).

The international demand for works by contemporary artists was extremely strong. Among the most anticipated lots of the sale was Apocalypse Now, recognized as the most important painting by Christopher Wool, which sold for $26,485,000 (estimate: $15,000,000-20,000,000), setting a new world auction record for the artist and far exceeding the previous record for the artist of $7.7 million. Executed with a raw power and gritty directness that gave new purpose to the medium of painting in the 1980s, this legendary statement of absolute nihilism makes it one of the most seminal works of contemporary art. The sale started with Wade Guyton’s Untitled, one of the rare examples with the artist’s signature fire motif to be presented at auction, which rocketed to $2,405,000 (estimate: $500,000-700,000), a world auction record for the artist.

The momentum continues today in our Day Sales of Post-War and Contemporary Art, while bidding remains open in our Online auction through November 19. I will be in touch again in the coming days to share further thoughts on this monumental moment in the art world.

Brett Gorvy

Chairman, International Head

Post-War & Contemporary Art

How to buy an Oriental Rug

(MONEY Magazine) – There I was in a Manhattan carpet dealer’s showroom enjoying a typical Persian lunch–charcoal-oven-baked chicken, rice, mint curry, roast tomato and tea–when my meal tray almost fell off my lap. “$30,000!” I blurted. David Zadeh, the proprietor of Symourgh International, nodded calmly–as did his 90-year-old father Moussa, a courtly retired rug dealer from Tehran. Just minutes earlier we had been looking at an antique 10-foot-by-13-foot Tabriz–an orange and beige Oriental carpet that, frankly, I thought was a bit garish. My reject was someone else’s treasure. And so I learned Oriental rug-buying lesson No. 1: Don’t price the merchandise while eating lunch.

That carpet–the price of a new BMW Z3 roadster–was far from the costliest one I’d see that week. Prices of Oriental rugs (which are generally no larger than six feet by nine feet) and carpets (which can be more than twice as large) have doubled since the late-’70s Iranian revolution reduced the number of fine rugs on the market. Prices should continue to rise smartly in the next decade, as newly flush baby boomers snap up these most luxurious of floor coverings. You can see why they’re in demand: A rug of even modest quality will most likely outlive you and your children (machine-made broadloom, by contrast, is ready for the landfill after five to 15 years). And the best Orientals are one-of-a-kind works of art that hold their value or even appreciate.

Problem is, not all Orientals are created equal–and unwary buyers can easily be taken on a financial carpet ride. The $1.4 billion Oriental rug marketplace is one of the few retail businesses in America where haggling is still expected. And comparison shopping is difficult, because no two carpets are exactly alike. So with my editors’ blessing, I set out to find out for MONEY readers how nonexpert buyers can get an heirloom-quality rug at a fair price. In the process, I learned another of the dangers of the Oriental carpet bazaar: It’s way too easy to fall in love with these unique (and expensive) beauties.

From my newspaper and magazine reading, I knew some fundamentals–including the fact that most Oriental rugs come not from the Far East but from the Middle East, notably the Caucasus, Iran (formerly called Persia) and Turkey. I also knew that the standard means of production–knotting short lengths of wool or silk yarn on a woven foundation–hasn’t changed in 25 centuries. And I’d taken a look at Orientals from time to time when wandering through high-end home furnishings stores–though I must confess most of the rugs seemed too brightly colored, even crass.

Once I began my assignment in earnest, however, I soon saw that many older rugs were exquisite, not crass. One of my guides was Mary Jo Otsea, head of the rugs and carpets department at Sotheby’s, the New York City auction house. Her office on the Upper East Side of Manhattan overlooks a brick-walled storage area in which rolled antique and semiantique rugs, each valued at $1,000 to $200,000, stand 10 and 15 deep, awaiting one of Sotheby’s triannual “rugs only” auctions.

Otsea walked me through the room, explaining that new rugs like the ones I’d seen in stores simply can’t compare with these antiques (made 100 or more years ago) and semiantiques (made 50 to 99 years ago). “These older rugs were made using natural vegetable dyes, as opposed to the chemical dyes used on younger ones,” she explained. “Years of use soften these colors and make the wool more lustrous.”

Rugs are typically identified by the city or region they come from, she said, and each tends to have distinct characteristics. For example, Kashans from central Iran usually have floral patterns and velvety pile; Kazaks from the southwestern Caucasus, strong geometric patterns and loose weaves; Ladiks from Turkey, colorful borders and a central arch design. (See the table on page B24 for some examples.) But virtually all Oriental rugs fall into one of two general categories, said Otsea: tribal or city. “The weave on a tribal rug is generally not very tight–as few as 50 knots per square inch–and the colors are bold,” she said. “Many tribal rugs have geometric designs because the looser weave limits the shapes a weaver could produce.”

City rugs are tribals’ sophisticated cousins. Weavers from Iranian cities like Isfahan, Kashans, Kerman and Qum typically followed intricate, curvilinear designs sketched on paper by palace artists. Some of their rugs have as many as 1,200 knots per square inch. A nine-foot-by-12-foot rose-red Kashans from the 1920s that Otsea pointed out, strewn with blue and beige flowers, might have taken three master weavers three to four months to complete. It would have taken me about five times as long just to save the $4,000 to $5,000 that Otsea estimated the rug would fetch at auction.

Prices of the best Orientals ripen with age, I was learning, and sometimes the process isn’t slowed even by obvious wear. While we sat in Otsea’s office, she reached down to a small rug at my feet. “This is a nice little piece,” she said, unfurling a four-foot-by-six-foot, azure-bordered beauty. “It’s a 17th-century Isfahan. You see where it looks worn out here?” She pointed to brown and black areas around the floral design that looked scraped almost down to the foundation, while the rest of the pile appeared untouched. “The natural dyes used to make brown and black often contained iron, and those areas are oxidizing.” Does that hurt a rug’s value? Not at all, said Otsea, who estimated its value at–gulp–$80,000 to $120,000.

According to Otsea, the two most important factors behind such a price are the rug’s adherence to its region’s weaving tradition and its artistic execution. Most serious collectors treasure tribal rugs more than city ones, in part because they better reflect age-old weaving traditions. “That’s not to say that a city rug won’t make a good heirloom,” she added. “City rugs in respectable condition from the most desirable regions, such as Isfahan, Kashan and Tabriz, will hold their value over time.”

As I got ready to leave, Otsea gave me the names of several top-end Manhattan rug dealers. Knowing rug merchants’ reputation, I asked how much I should trust the prices they quote. Most legitimate dealers leave themselves 10% to 15% haggle room, she explained. Best advice: Start by offering 20% below the ticket price and negotiate from there. On my way out, she gave one final word of advice: “Never buy a rug at going-out-of-business sales or itinerant auctions”–those two- or three-day extravaganzas that are often held at hotel ballrooms and advertise huge discounts. “The rugs are never as good as advertised, and they’re often overpriced.”

Armed with her insights, I headed straight to an Armenian church for an itinerant sale that had been advertised in the New York Times. While my wife Mary listened to a salesman’s mile-a-minute pitch–“This Persian rug was made 40, maybe 50 years ago, all handwoven and only natural vegetable dyes”–I parted the cream-colored pile on the $6,785 rug he was hawking and discovered red dye at the base of the knots. Clearly, the manufacturer had used shoddy dyes that ran and had probably washed the rug chemically to give it the appearance of age. When I brought the problem to the salesman’s attention, he didn’t miss a beat. “What, you don’t like this one? Let me show you something you like.” No, thanks.

Returning to Otsea’s list of respectable dealers, I went first to Symourgh International, a block from the Empire State Building. The rugs Zadeh showed me were just as lovely as the ones at Sotheby’s and often in better condition–such as a semiantique nine-foot-by-12-foot Bukhara from Turkistan, deep red and cream with characteristic rows of hexagons, called guls. The pricing, however, had more than a little wiggle in it. I couldn’t induce Zadeh to give me a single firm price; at most he would give me a range ($7,000 to $8,000 for the Bukhara, for example). “There are no set prices for rugs, as for all antiques,” Zadeh explains. That’s typical, I learned.

Next stop: Darius, a dealer on East 57th Street who had been recommended by another of my sources, independent appraiser and Oriental rug scholar Posy Benedict. Darius sells 90% of its wares to decorators. Proprietor Darius Sakhai, a London-educated fourth-generation rug dealer, told me that city carpets with soft colors and subtle “overall” patterns (that is, no center medallions) are the most sought after now. “I don’t even look for the traditional red and blue rugs with dark backgrounds,” he said. “Most of the people buying from me have modern furniture and important works of art on their walls. They don’t want the rug to be the focal point of the room.”

Then I saw it: the most beautiful rug of my weeklong foray. It was a 12-foot-by-18-foot beige and tan Tabriz in a so-called garden pattern, where the central motif consists of rows of boxes reminiscent of a classic Persian garden. The colors were so subtle that it looked as though the artist had drawn in sand. Expensive sand–the carpet cost $110,000 (this dealer didn’t shy from exact prices). I figured he might come down to $95,000 or so, and for a brief moment I calculated how much I could borrow from my 401(k), mentally ran up the borrowing limits on my credit cards and…okay, okay. Enough dreaming. “Nice colors,” I said.

After a long, parting gaze at the Tabriz, I moved on to the cozy Fifth Avenue gallery of Doris Leslie Blau, reputedly the grande dame of New York City carpet dealers. Blau proudly showed me a seven-foot-by-23-foot, early-19th-century northwest Persian carpet with pastel ribbonlike designs on a blue field. “I first sold this carpet in 1978 for $13,000,” she said. She bought it back from the buyers 10 years later and is now asking $85,000. Even if she gets 15% less, that’s still an average annual rate of return of nearly 10%–quite respectable, if not as high as the 15.8% average annual gain for the S&P 500 during the same time period.

How can ordinary buyers identify rugs with that kind of investment potential? I put the question to Posy Benedict, who sighed deeply. “Predicting which rugs will appreciate is an extremely uncertain business,” she said. “But if you buy a charming piece in very good condition, with beautiful colors and a crisply drawn design, chances are good its value will increase.” The best strategy for buying a rug you plan to put on your floor, she said, is to spend $15,000 to $50,000 on a semiantique from around the turn of the century. While the rug you choose can show signs of wear, it should not be worn to the degree that the pattern is obliterated. Semiantiques in good shape should last at least 50 to 150 years on your floors, even when subjected to daily foot traffic; rugs with a knot count of 200 per square inch or more generally last longer than those with lower counts.

The appreciation potential of new rugs is chancier than that of antiques or semiantiques, added Benedict. If you are determined to buy a new carpet anyway, choose a high-quality classic Persian design handwoven in Egypt or Turkey and made with natural dyes. Because the investment outlook of any rug is never a sure thing, stressed all the experts I spoke with, buy only a specimen you truly love.

More buying tips:

–Do some research before you shop. One comprehensive guide is Sotheby’s Guide to Oriental Carpets by Walter B. Denny (Simon & Schuster, $16). Also consider calling Christie’s (800-395-6300) and Sotheby’s (800-444-3709) to request copies of recent rug sale catalogues (typical price: $30 to $35 each); they include photographs of scores of rugs and carpets, along with their estimated selling price.

–Check that the rug is in good condition. Steer clear of rugs that have been subjected to merely cosmetic repairs–for example, on which paint has been applied to hide a badly worn spot. By contrast, careful restoration, where the rug is actually partially rewoven on a loom, will often add strength and years to the piece without greatly diminishing its value.

–Find a reputable dealer. Ask friends who’ve bought rugs recently for recommendations, then check with your local Better Business Bureau to see if any customers have filed complaints against the dealer in the past three years. Stick with a dealer who has been in business for at least 10 years and offers either a money-back guarantee or, at least, a liberal exchange policy.

–Alternatively, consider an established auction house such as Christie’s or Sotheby’s in New York City, Butterfield & Butterfield in San Francisco, Skinner in Boston or Leslie Hindman Auctioneers in Chicago. “You’ll get the biggest bang for your buck at auction,” promises James French, the resident rug expert at Christie’s. (Once you buy the rug, however, you own it.) Before the auction, attend the preview, at which you can look at the merchandise up close and ask questions of specialists on hand.

With diligence, patience and a bit of good judgment, you can get a beautiful rug that’s worth the money you paid. But keep your hands off that Tabriz. It’s mine.

Rugs and the Persian Culture

Did you know that carpet weaving is the most distinguished manifestations of Persian culture and Art.

A few years ago Iran’s exports of hand woven carpets was over $400 million, roughly about 30% of the whole world’s market.

There are about 1.2 million carpet weavers in Iran that produce carpets for domestic and international markets. Iran exports carpets to over 100 countries. Understanding oriental carpets and their main theme means understanding the meaning of all their intricate designs and motifs. Their patterns is an intimate expression of a people’s history, faith and civilization.

Hello world!

Welcome to WordPress. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start blogging!